University Course Examines Race, History and Higher Education in the South

Course explores the role Duke, other Southern universities play from slavery to current day

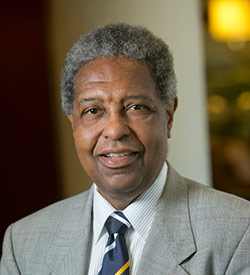

This semester, William “Sandy” Darity is putting Duke – and other universities -- under the microscope.

Darity, the Samuel Dubois Cook Professor of Public Policy at Duke, is the lead professor this semester for a University Course examining race and higher education. In it, Darity and other faculty members analyze the role Duke and other universities throughout the South have played from slavery to modern times.

Darity, the Samuel Dubois Cook Professor of Public Policy at Duke, is the lead professor this semester for a University Course examining race and higher education. In it, Darity and other faculty members analyze the role Duke and other universities throughout the South have played from slavery to modern times.

The University Course format was introduced in 2012 as a way to offer a sweeping course with multiple faculty voices on a single theme. (Previous University Courses have tackled issues surrounding water, food and housing). Thus far, faculty members Thavolia Glymph in History and African-American Studies, Robert Korstad in the Sanford School of Public Policy and History, Martin Smith in the Program in Education, and Gwendolyn Wright at the Cook Center have contributed.

Here, Darity speaks with Duke Today about the course and its relevance to today’s college students.

Q: In the syllabus, you write that this course will include ‘the examination of why the Southern system of racial stratification was embedded in Southern higher education.’ Were Southern universities in the 1800s perfectly reflective of the more broad Southern culture – in which racial stratification was, of course, pervasive? Or were they slightly or significantly more progressive?

DARITY: I contend that Southern universities were so deeply implicated in slavery and Lost Cause ideology that I am hard pressed to claim they were more "progressive" than the society at large. Antebellum colleges and universities owned enslaved persons, relied significantly on their unpaid labor, and received donations of funds and land from whites who built their fortunes on slavery and the slave trade. Generally, but especially in the South, black students and faculty were excluded uniformly from these institutions.

Northern universities weren’t particularly progressive either, even the most prestigious: Harvard, Yale, Princeton, Columbia, Brown, Dartmouth, Penn, etc. Plus scholars at these institutions made the "scientific" case for black inferiority, distorted the story of the Reconstruction Era, and crafted the narrative of slavery as a benign "school for civilization."

Q: This is a University Course, meaning it is taught by several faculty members and is open to students at all levels – undergrad and graduate alike. Why is this particular topic important to students here at Duke?

DARITY: It's essential for all of our students to have an improved understanding of the accurate historical record. It's also important for all of our students to have an understanding of the place position and consequences of American universities, especially those in the South. That's particularly important because Duke is a Southern university. Having our younger undergraduates take this course means that, hopefully, it will affect the range of questions they ask and classes that they take subsequently.

Q: A section of this course tackles race and the professoriate – the challenges facing female and minority scholars in finding work in Southern higher education. Is progress being made on that front, and if so, where? Publics? HBCUs? Private elite institutions like Duke?

DARITY: I think that this depends upon the particular discipline. For example, in my own field of economics there is a decided absence of black scholars even at state institutions in states with a high black proportion of the population. Under representation remains a critical problem for us all colleges and universities both South and North. But the problem is more severe in some disciplines than others. Gregory Price has found, for example, that there is an inverse relationship between the increase in the numbers of blacks with PhDs in economics and the numbers of blacks hired by PhD-granting economics departments.

Q: Is there a topic you tackle in this course that is most likely to surprise students?

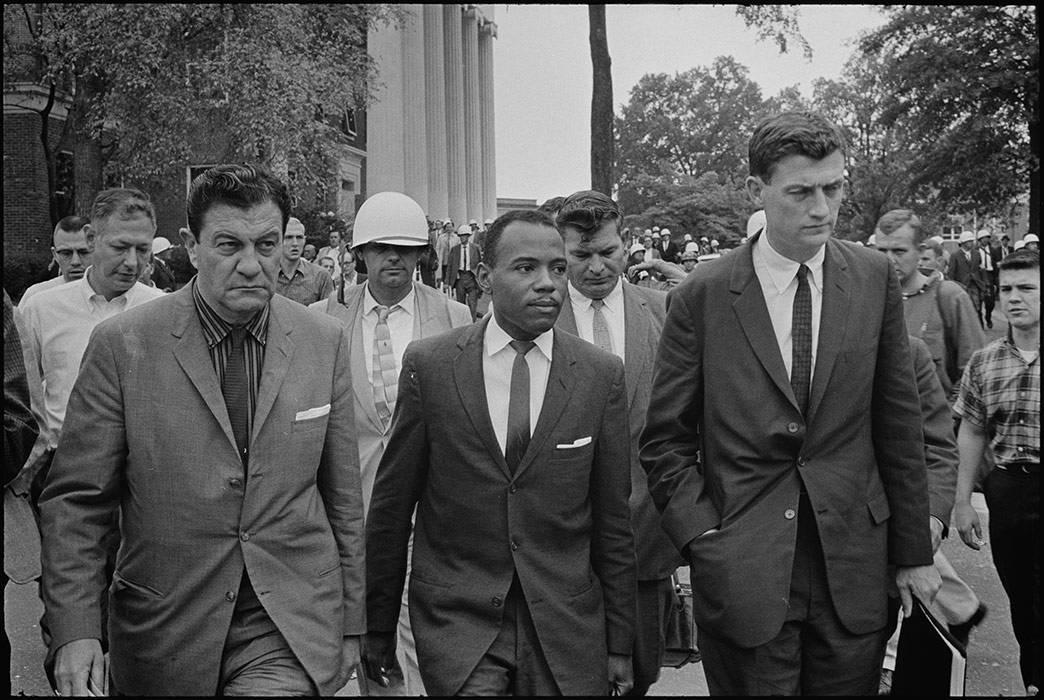

DARITY: I think there may be a host of surprising discoveries for students who are taking the class. But one that I might highlight is the extent to which black students who were in the first wave of students who desegregated these institutions experienced post-traumatic stress disorder because of the racism they encountered.