Inaugural Trinity Distinguished Lecture to Feature Mark Anthony Neal

Lecture part of college's commemoration of 50 years of Black faculty scholars at Trinity

Mark Anthony Neal, a professor in the departments of African & African American Studies and English, will give the inaugural Trinity Distinguished Lecture on Thursday, May 4, at 3 p.m. in Penn Pavilion. His talk is open to the public and will be followed by a reception.

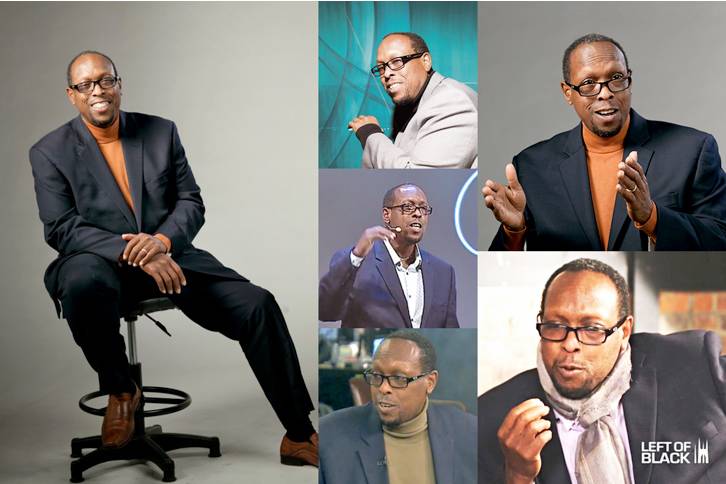

Through his research and public outreach, Neal challenges audiences to engage with Black popular culture. He is the editor and curator of the NewBlackMan (in Exile) blog, he hosts and produces the Left of Black webcast and has a combined Twitter following for the two outlets of nearly 65,000 people. Neal seeks to understand how the music, television, film and literature of African diaspora culture influences the societal and cultural norms of the United States and around the world.

Below, Neal discusses his academic pathway and the issues he'll cover in Thursday's talk.

Can you explain the title of your talk: My Mother Gave Me This Big-Ass Name: A Black Scholar in the Mix?

MARK ANTHONY NEAL: The talk title is inspired by my relationship with my late mother, and the fact she encouraged me at a very young age to embrace all three of my names—even to the point of her being conscious that my three names spell out the acronym MAN. My parents were working class, actually working poor, and they invested quite a bit for me to be successful.

My mother hoped that I would grow into the name she gave me. I was a first-generation student (my mother and I were in college at the same time) and a state college dude (shout out to SUNY). My father was a so-called “functional illiterate,” yet still my first and most cherished interlocutor. I hope that I’ve lived up to their hopes.

Music features strongly in your academic research. Does "Black Man in the Mix" refer to music?

NEAL: I largely interpret the world through music. My taste can be eclectic: everything from Kendrick Lamar to classic ‘70s Chicago, The Soul Stirrers, Miles Davis, Patsy Cline and Erykah Badu—but more specifically as one long musical mix. I am thankful for the gift that was my father’s own love of music. I still have cassette tapes—pause button mix-tapes that I made as a teenager in the Bronx, more than 30 years ago.

MAN on Race and Baseball

With a large following in social media and a capacity for offering challenging perspectives on contemporary issues, Mark Anthony Neal is regularly sought out for comments in national media. Below, in an opinion piece published in The Detroit Free Press and other newspapers, Neal takes on why the racial taunting of Adam Jones in Boston’s Fenway Park shows how race remains a pressing issue for baseball and America, 70 years after Jackie Robinson’s debut.

Read the article here.

I view the playlists that I've curated on the streaming services I use as intellectual property. In many ways, my writing style and ability to write differently for different audiences is a by-product of viewing ideas in the context of a mix. It drives my natural inclination to put disparate ideas and voices in conversation with each other, like Black feminist icon Audre Lorde and Hip-Hop mogul Jay Z.

Why do you do so much public outreach?

NEAL: As a graduate student in the early 1990s, I was profoundly impacted by public intellectuals like author/social activist bell hooks, professors such as the late African-American historian Manning Marable, and Georgetown Professor Michael Eric Dyson, who I am privileged to call a mentor and friend. They were rock stars.

But I was also impacted by journalists, filmmakers, producers and music critics like Nelson George and Greg Tate; newspaper sportswriter Mike Lupica, and satirist Russell Baker, whose "Saturday Observer" column in the New York Times was a favorite of mine as a teen. In short, I wanted to be read.

The biggest influence though was the late television journalist Gil Noble whose public affairs program “Like It Is”, a public affairs television program focused on issues relevant to the African-American community, was my introduction to Black politics. The first time I saw a clip of Malcolm X was while watching “Like It Is.”

My own program, Left of Black, is largely a tribute to Noble's influence on me. My career has largely been devoted to idea that some of the work that I produced would be of value to folks like my parents, who were never going to experience an elite institution like Duke, or in some cases weren’t afforded even a nominal public education. I never lost sight that I am a working class cat from the Bronx, a child of labor unions, the Third Avenue El and soul music on transistor radio in the summer while sitting on the stoop.