Dancing the Story of Hayti, Haiti, and Durham

Power Plant arts residency explores lost stories of Durham's African American history

“Whooooo!” Aya Shabu belts out the shriek of a factory whistle in the Power Plant Gallery as she and Dasha Chapman begin a narrative dance about the African American women who processed tobacco in Durham’s cigarette factories.

During open studio hours, the dancers develop a performance that imaginatively depicts the cultural and historical connections between Haiti and Durham’s Hayti (pronounced hay-tie) neighborhood. Through dance and oral narrative they have embodied the experiences of the African Americans who came to Durham to work in the tobacco factories.

The dancers move around as if the gallery was made for performance, but this project is part of the summer transformation of the Power Plant Gallery, as it welcomes the #PPGArtists in residence. Normally home to works of art, the gallery which was founded by the Center for Documentary Studies and Duke’s Master of Fine Arts in Experimental and Documentary Arts program, has been turned into an artist studio.

Shabu and Chapman completed their six-week residency last weekend with a performance of their piece. Sculptor Julia Gartrell started the second residency on July 19.

Power Plant Gallery Director Caitlin Margaret Kelly said the residencies further the gallery’s interest in linking art and documentary history.

“Both residencies explore regional and personal identities and histories, each through their own artistic medium,” Kelly said. ”Their projects, rooted in scholarship, oral histories, place, and time also reinforce the arts as a form of inquiry and critique.”

The artists have 24/7 access to the Power Plant Gallery to use the space as a studio. They hold open studio hours during which members of the public can pop in and check out the art in progress.

Shabu is an alumna of the African American Dance Ensemble, a teaching artist for the Durham Arts Council’s Creative Arts in Public and Private Schools (CAPS) program, and the founder of Whistle Stop Tours. Her dancing partner, Chapman, worked as a postdoctoral associate in the Department of African and African American Studies at Duke.

Among many stories that the dancer’s project tells are those of African-American workers who left rural North Carolina to take jobs in Durham’s tobacco factories and settled along Fayetteville Road where they established Hayti. These new residents of Durham established successful African American owned businesses, insurance companies, and vibrant religious and social institutions.

Many of Hayti’s residences and commercial buildings were demolished during “Urban Renewal” and the building of North Carolina Highway 147. Through the efforts of the community, St. Joseph’s AME Church survived. The original building has been preserved and now serves as the Hayti Heritage Center a place where residents and visitors gather for cultural and civic events.

When Chapman moved to Durham, she began taking African dance classes at the Hayti Heritage Center where Shabu and her company, Shabutaso, host one of the largest annual Kwanzaa celebrations in the Triangle.

Chapman became curious about the name Hayti because of her travels to Haiti to work with local choreographers. Yet much of the history of Hayti has been lost and the stories of its Haitian ties forgotten, Shabu said.

“I asked somebody if there was any connection between Hayti and Haiti and they told me no,” said Shabu. “But I just couldn’t believe that was true.”

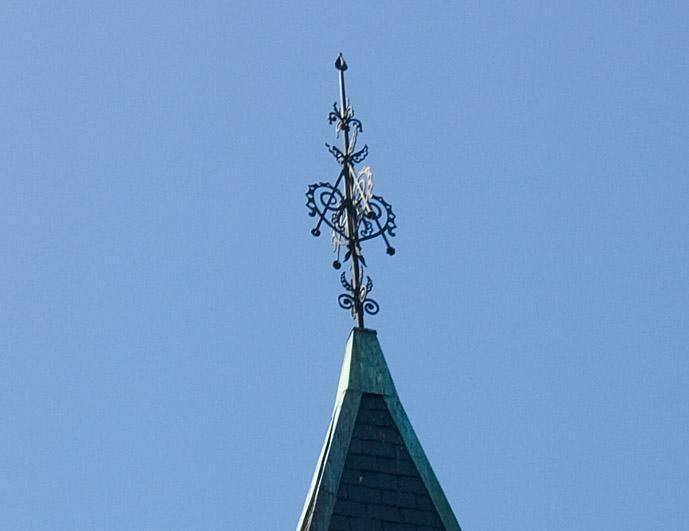

It was the steeple shaped like a Vèvè atop the old St. Joseph’s church that sparked her curiosity about the community. Vèvè are religious symbols in Haiti and found throughout the African Diaspora.

Finding such a prominent link to Haitian culture in Hayti led to further research about the history of Hayti and its residents. The artists found that Haiti, the Western Hemisphere’s first free black republic, may have been the inspiration for the founders of Hayti, which had close connections to Durham’s “Black Wall Street.”

“When we’re thinking about those people, many of them didn’t have any direct connection to Haiti,” said Shabu. “So on some level they were imagining what Haiti was ... after hearing that there was this free black country, maybe a promised land to some extent.”

The open studio hours were an important part of the research during the residency. The dancers said being prepared to share their art while it’s still in progress can be very motivating. For Shabu and Chapman, the chats they had with their guests were rewarding.

“A woman from India who works nearby came into the studio and saw videos of people drawing Vèvè in Haiti,” said Chapman. “She started telling us about the drawings that she and the women in India draw on the doorsteps every morning at sunrise, called Rangoli. We had this beautiful conversation about this practice that’s different but shared.”

Although the dancers have moved out, their work continues. You can follow it on their blog “Hayti Haiti History.” The Power Plant Gallery is still holding open studio hours on select weekends. The current resident Julia Gartrell will create a series of sculptures about the history of labor and agriculture in Durham, viewed through the lens of the tobacco industry.