Moving Duke and the World Forward

Duke’s comprehensive fundraising campaign advances ideas, fosters new connections

Like many gifts in the Duke Forward campaign, Sue Wasiolek’s had its roots in her past.

Wasiolek, Duke’s associate vice president for Student Affairs and dean of students, allocated some of her bequest to where she has time-tested connections: Duke’s Annual Fund, a godsend for university administrators like her, and the Duke Football program. She’s missed just one home game in four decades.

The bulk of her gift went to financial aid. Without it, she would have never have made it to Duke. Financial support allowed her parents, who worked nights as a security guard and check processor, to pay $73 for her Duke undergraduate education.

“That was a game-changer for me,” said Wasiolek, who has three Duke degrees and has worked at Duke since the late 1970s. “But for that, I would have never been at Duke.”

While donors’ personal histories shaped many contributions, Duke Forward was about what’s coming next. The nearly decade-long campaign, which touched all 10 of the university’s schools and health system, aimed to enrich the student experience, attract the brightest minds and position Duke to respond to challenges in an increasingly complex world.

The goal: raise $3.25 billion. As the campaign crossed the finish line this summer, $3.85 billion had been raised with the help of more than 315,000 donors and foundations.

“Duke Forward has been a tangible demonstration of how much people care about Duke and believe in its future,” said Duke University President Emeritus Richard H. Brodhead, who presided over the campaign from its 2010 launch to its conclusion June 30, 2017.

While aimed at the future, Duke Forward has shaped the present.

Donors contributed $473 million for financial aid and fellowships while other gifts enabled Duke to renovate historic buildings, establish endowed professorships, support experiential learning programs, and fuel groundbreaking medical advances.

“This is a place that is known by people around the world as being where you can come and have a good idea and it’s going to happen,” Wasiolek said.

And in many cases, it’s already happening.

Bringing in the best

For Beverly McIver, seeing non-art majors behind easels in her painting classes is a special thrill. She knows they’ll attack the challenge of creating art with the same diligence they reserve for tests in their chosen disciplines.

But, she tells them that, in art, it’s not always about finding the correct answer.

“I tell them ‘I want you to make mistakes, I want you to fail at this initially because you’re going to learn so much and it’s going to make you a better artist,’” McIver said. “Once they grasp that, they’re willing to take risks and color outside of the box, which is exactly what I want them to do.”

Since 2014, McIver has been the Esbenshade Professor of the Practice of Art, Art History and Visual Studies, one of 85 endowed professorships that sprang from the Duke Forward campaign.

Earning praise for vibrant, textured portraits, McIver recently received the 2017-18 Joseph H. Hazen Rome Prize from the American Academy in Rome. She came to Duke from a tenured position at North Carolina Central University. Part of the allure was the promise that inspiring students’ creativity would be the central pillar of her work.

“I’m passionate about my craft and what I do,” McIver said. “It’s my livelihood, so the opportunity to pass it on to young people and get them excited about it has always been an important goal.”

Building the future

At Duke’s Human Simulation and Patient Safety Center, the drama is real even if the patients aren’t.

Virtual patients tell medical students about symptoms through computer screens. Mannequin patients receive care while instructors in control rooms simulate cardiac arrest and equipment malfunctions.

“In healthcare, things don’t always go like you expect them to,” said Jeff Taekman, professor of anesthesiology and the center’s director. “Here, we can do a lot of those unexpected situations without putting patients in harm’s way.”

The center, housed in the Mary Duke Biddle Trent-Semans Center, is a valuable tool for Duke University School of Medicine. The six-story, 104,000-square foot Trent-Semans Center opened in 2013 and was the first building constructed exclusively for the medical school since 1930.

Most of the Trent-Semans Center’s $53 million cost was covered by money raised during Duke Forward. The campaign raised money for several other building projects. Many of them, including renovations to Brooks Field at Wallace Wace Stadium, Duke University Chapel and Brodhead Center, are complete.

The Trent-Semans Center has given the School of Medicine, previously scattered around Duke’s sprawling hospital campus, its own state-of-the-art home.

“Everybody just had big grins on their face when the building opened,” said Edward Buckley, the School of Medicine’s vice dean for education. “It fit the needs that we had.”

Expanding students’ horizons

In 2015, Raphael Kim, a Duke first year student with a passion for math, saw a flier seeking help with an image processing project.

Two years and one centuries-old painting later, he’s on a team at the forefront of art conservation.

“Totally not what I expected,” Kim said.

These stories are the goal of Bass Connections, which received $90.8 million during Duke Forward, including a $50 million gift from Anne and Robert Bass.

Since 2013, Bass Connections, one of several educational programs created during Duke Forward, has helped 176 teams of faculty, graduate students and undergraduates tackle subjects in health, education, energy and culture using a global, discipline-spanning approach.

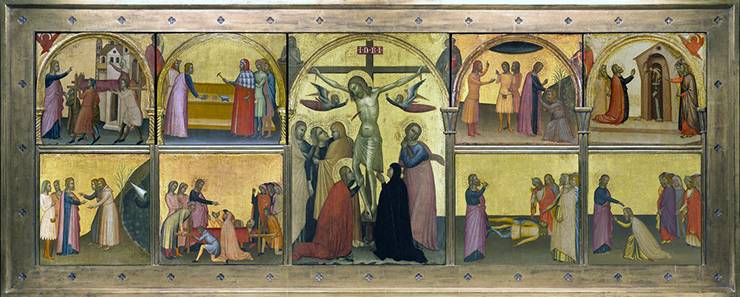

Kim’s project began when the North Carolina Museum of Art planned on exhibiting eight existing panels of Francescuccio Ghissi’s 14th-century altarpiece depicting the life of St. John alongside a recent reconstruction of the missing ninth panel.

Using image processing algorithms, the Bass Connections team of mathematics, computer science and mechanical engineering students, led by mathematics professor Ingrid Daubechies, virtually aged the new panel to match the others. The same techniques refreshed the old panels, showing the piece as it looked 650 years ago.

“What Bass Connections made possible was the fluidity of it all,” Daubechies said. “I could have an idea and I had a little bit of money to actually realize it. That made all the difference.”

Now, the team is weaving these image rejuvenation techniques into a mobile app.

“It’s pretty funny,” Kim said. “When I came to it, I had no idea I’d be working on something like art history.”