Making the Unseen Visible: Chan Zuckerberg Initiative Invests in Duke Imaging Technology

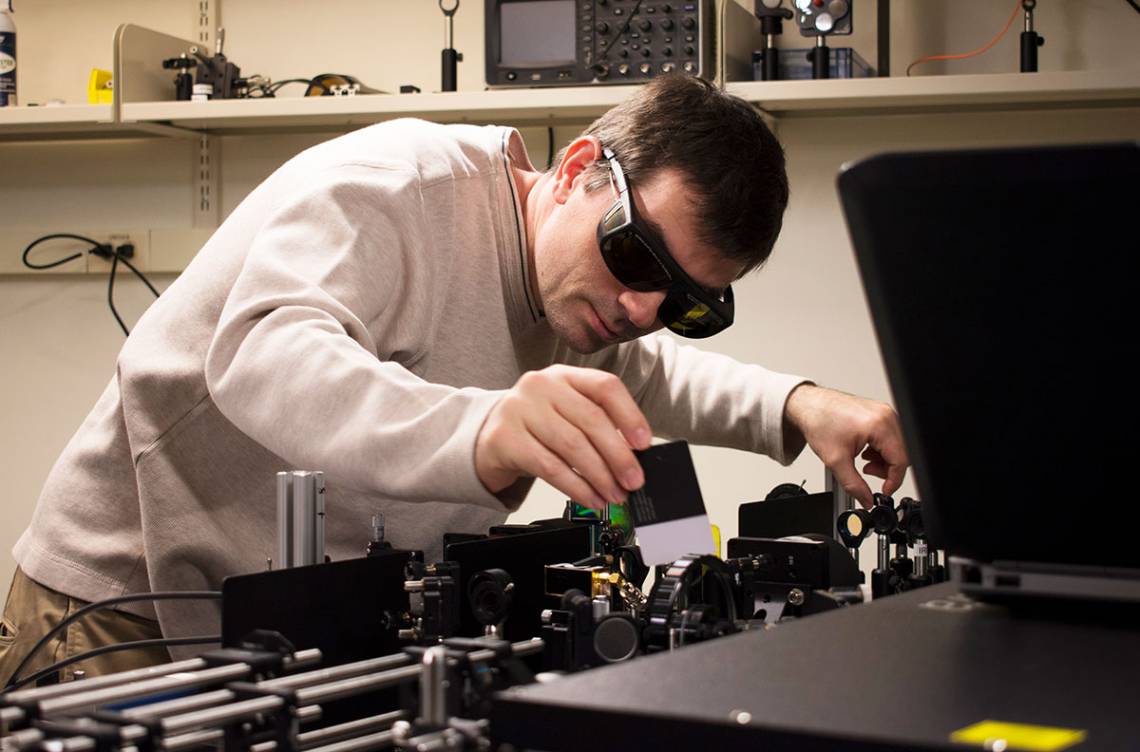

A scientist working in optical spectroscopy and microscopy techniques at Duke has been awarded more than $670,000 by the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative (CZI), the organization announced March 19.

Martin C. Fischer, associate research professor in chemistry and physics at the Trinity College of Arts & Sciences, received the funding related to the new Advanced Light Imaging and Spectroscopy (ALIS) facility, which he directs. ALIS’ focus is developing novel instrumentation to visualize the physical structure of and chemical information in complex materials. Access to those instruments will be offered broadly across Duke.

“Microscopy is a critical tool that allows researchers to actually see biology and life happen instead of just inferring from disparate data points," said CZI co-founder Priscilla Chan. "Our hope is that microscopy will help scientists identify the causes and effects of diseases. We need to keep advancing these tools to make big breakthroughs in understanding disease.”

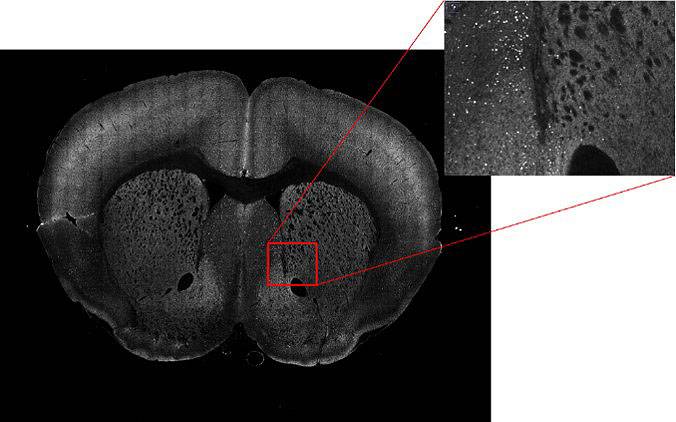

The ALIS facility opened in 2018 in the French Family Science Center. Some of the lab’s microscopes study small samples at very high rates, such as the real-time monitoring of developing fly embryos. Others enable studying large samples at slower rates, such as the distribution of genetically labeled cells in an entire mouse brain.

The ALIS facility opened in 2018 in the French Family Science Center. Some of the lab’s microscopes study small samples at very high rates, such as the real-time monitoring of developing fly embryos. Others enable studying large samples at slower rates, such as the distribution of genetically labeled cells in an entire mouse brain.

Beyond the use of these instruments in natural, basic and clinical sciences and engineering, Fischer’s work with the microscopes may also support research in fields such as arts conservation.

“The microscopy techniques I develop might help evaluate treatment methods for skin cancer, help understand the limits of efficiency in new solar cell materials, or determine why certain pigments in a Renaissance artwork fade or change color,” he said.

That interdisciplinary potential will also enable the transfer of technology between multiple disciplines that encounter similar problems in imaging.

“Duke already has an outstanding Light Microscopy Core Facility that provides researchers at all levels – from faculty to postdocs to grad students and undergrads – with commercially available instruments. ALIS is positioned to provide state-of-the-art microscopes that are not yet commercially available,” said Dan Kiehart, dean of Natural Sciences and professor of biology in Trinity College.

“Such instruments are designed to push the limits of super-resolution and will impact biology and materials science in Trinity, the Pratt School of Engineering, and the School of Medicine. It will enable curiosity-driven research into biological mechanisms that go awry in pathogenesis.”

“It is quite satisfying to make something visible that could not be seen before,” Fischer said. “Microscopy can offer a glimpse into the structure and function of systems that we cannot see by eye. Looking beneath the surface of skin, looking at chemistry within the cell, or visualizing the workings of a solar cell offers plenty of answers as well as surprises.”

Fischer is among scientists representing 17 imaging centers across the United States to receive the CZI funding. This project has been made possible in part by a grant from the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative DAF, an advised fund of the Silicon Valley Community Foundation.