Blue Devils, Green Thumbs

Across Duke, office plants provide a living connection to workspaces

On shelves, near windows and tucked into winding corridors of the Duke Graduate School’s rambling offices, there are many splashes of green.

From small, spiked cactuses to lush, flowering lilies, the building’s offices and common areas are filled with plants. And many of them are cared for by staff assistant Lynette Roesch.

She looks after the philodendron vine that climbs the bookcase in the office of Assistant Dean for Budgets and Finance Iryna Merenbloom and the ZZ plant that shoots skyward in the office of Alan Kendrick, assistant dean for graduate student development.

And Roesch knows that, of all offices in the building, Staff Accountant Tammy Dickens has the space plants love most.

“There are some good, green vibrations in this office,” Roesch said while standing in Dickens’ southern-facing workspace. “Any plant put in here, grows better than anywhere else.”

For Roesch and many other Duke staff and faculty, caring for office plants does more than help make surroundings prettier. They offer a living connection with workspaces and provide moments of constructive relaxation.

“I think it’s important to have a living thing in your working environment if you can,” Roesch said.

We caught up with some of Duke’s greenest thumbs to get their thoughts on how to get the most out of your office plants.

Put thought into watering

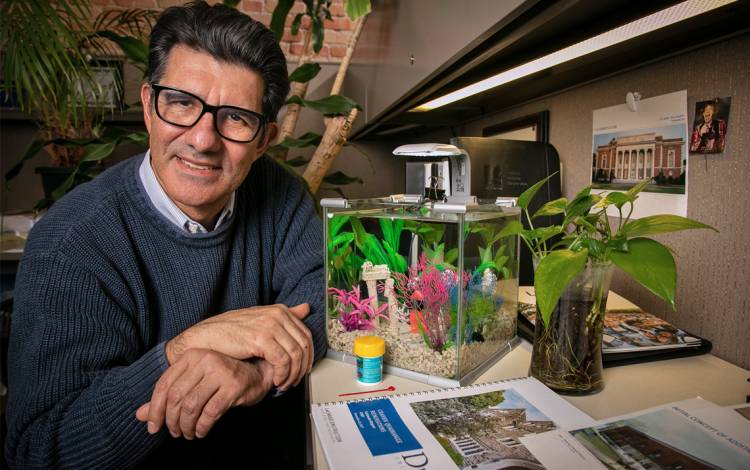

Alphonso Alonzo shares his Smith Warehouse workspace with a few companions: his red-and-blue betta fish named Mick – after Rolling Stones front man Mick Jagger – and a palm tree whose sweeping fronds shoot out of a large pot.

“I don’t have a window, so this is the second-best thing,” said Alonzo, a project manager for Duke Facilities Management. “It’s just me, Mick and the plant.”

Every two weeks, Alonzo changes the water in Mick’s tank. Instead of dumping the water – which contains nutrients from waste and uneaten food – he uses it to feed the palm.

“I’m just trying to use the stuff in the water to take care of the plants,” Alonzo said. “It’s better than throwing it down the sink. And plants love it.”

Watering is the most common chore associated with caring for plants. But as Beth Hall Hoffman, the Paul J. Kramer Plant Collections Manager at Sarah P. Duke Gardens points out, it’s not always simple.

“When people have trouble with plants, it usually has to do with watering,” she said. “They’re either overwatering or underwatering.”

How much water to give a plant depends on the plant and its pot. Wilting, yellowing leaves are a warning sign that plants are receiving too much, or too little, water.

It’s worth noting that plants require less water in winter months when they naturally go dormant. Also, glazed ceramic pots hold moisture more than their clay counterparts, so plants in them will likely require less water.

Listen to your plants

Duke Health Technology Solutions IT Analyst Regina Leak jokes that she’s so close with plants in her University Tower workspace that she talks to them.

Clustered around her desk and rising on shelves near her window, Leak has a thriving peace lily that’s roughly 10 years old, an African violet that provides large, purple blooms each summer and a Christmas cactus that had small, pink blossoms emerging from its hard, gnarled leaves well into winter.

“When I come in here, they just give me life,” Leak said. “I just want to say ‘Good morning’ to them.”

But it’s not the talking that Leak said has allowed her to be surrounded by so many happy plants, it’s the listening.

“They will let you know if they’re not happy,” Leak said.

Experienced gardeners can diagnose a plant’s issues by reading signs it sends. For instance, small leaves likely mean a plant isn’t getting enough water. Or if stems grow especially long, a plant may be searching for more light.

Hoffman said to keep watch for signs of pests or disease – such as discolored or misshapen leaves – and, if spotted, separate those plants from others to keep the problem from spreading.

While Leak’s office garden showcases her ability as a gardener, it also helps dispel a common misconception about where office plants can thrive.

Her window faces north, meaning it doesn’t get any direct sunlight. But her plants are still green and lush, which shows that for many common indoor plants, any light source – even artificial ones – can work.

“A lot of houseplants are tropical forest floor plants, so they’re used to not getting much light,” said Hoffman, who also coordinates Duke Gardens’ spring and fall plant sales. “So there are plenty of plants that will do well in an office.”

Don’t be afraid to experiment

Lynette Roesch has always had a love of plants. She started tending to her own houseplants as a teen and one of her first jobs was at a greenhouse.

“It’s something that’s always given me joy,” Roesch said. “I love to see things grow.”

When she came to the Duke Graduate School in 2014, she seamlessly slid into the role of the building’s unofficial horticulturist. She’s constantly trying to connect office plants with ideal conditions, whether a perfect amount of light or pot that gives plants enough room to thrive.

For many people, it’s that endless process of trial and error that makes caring for plants fulfilling.

“It’s like a science experiment,” Roesch said. “It’s fun.”

Love plants? Visit Sarah P. Duke Gardens. Learn more at gardens.duke.edu