Duke's History Reaches Far Afield

Duke has been in Durham for over a century, but pieces of its past can be found elsewhere

When Elizabeth DuRocher, a volunteer archivist with the Duke Medical Center Archives, was handed a handful of boxes to reprocess in 2017, she didn’t know she was going to get a rare opportunity to dig deep into a largely forgotten chapter of Duke’s past.

For roughly 40 years, Duke operated Highland Hospital, a small institution in Asheville. And it was DuRocher’s task to go through boxes of records to ensure papers, photos and blueprints were in order and to update the finding aid to help future researchers.

“It’s not a huge collection,” DuRocher said. “But it’s dense. The collection has a lot of information in it.”

In 1939, Duke took over Highland Hospital, which had been operating in Asheville’s Montford neighborhood since 1906. Duke ran the facility until selling it in 1980.

Duke’s current story is being written on campuses, hospitals and clinics scattered throughout the state, and even locales as far away as China and Singapore. But there are places, like Asheville, where now-closed chapters of Duke’s story have unfolded. Here are a few of them.

Duke Homestead

Since 1974, the Duke Homestead State Historic Site in northern Durham, has told the story of the Duke family and the tobacco empire that forever changed Durham. But for nearly five decades prior to being owned by the state, the 37-acre property belonged to Duke University.

The farm was where Washington Duke first grew and processed tobacco in the 1850s. Later, he and his sons – most notably James B. and Benjamin Duke – would transform the family operation into the American Tobacco Company, at one point the largest tobacco company in the world. The Duke family moved away from the farm in 1874 and by the 1920s, the property had fallen into disrepair.

The farm was where Washington Duke first grew and processed tobacco in the 1850s. Later, he and his sons – most notably James B. and Benjamin Duke – would transform the family operation into the American Tobacco Company, at one point the largest tobacco company in the world. The Duke family moved away from the farm in 1874 and by the 1920s, the property had fallen into disrepair.

Following the death of Benjamin Duke in 1929, and James B. Duke four years earlier, there was a push to honor the men who built a legacy of philanthropy. So with the help of Mary Duke Biddle, Benjamin Duke’s daughter, the university purchased the property and, after five years of repairs, opened it to the public.

“They ran it as a tourist attraction,” said Duke University Archivist Valerie Gillispie. “They would take students out there. It was a memorial of sorts.”

Trinity

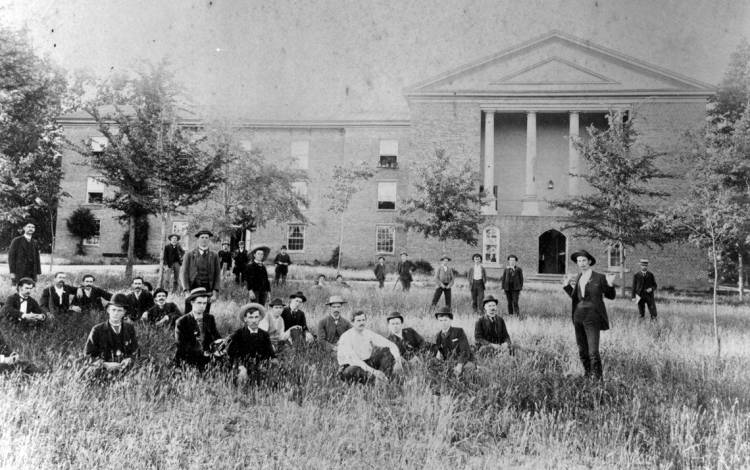

The deepest roots of Duke University’s history can be found in the small town of Trinity, in northwest Randolph County. It was here in 1838 that Brantley York began teaching area students in Brown’s Schoolhouse, which eventually became Union Institute and later Trinity College.

For more than 50 years, the school operated in Trinity under the leadership of presidents York, Braxton Craven and John Franklin Crowell. But citing challenges of a rural setting – there wasn’t a railroad, telegraph or telephone within five miles of the single-building campus – Crowell engineered the move to Durham in 1892.

For more than 50 years, the school operated in Trinity under the leadership of presidents York, Braxton Craven and John Franklin Crowell. But citing challenges of a rural setting – there wasn’t a railroad, telegraph or telephone within five miles of the single-building campus – Crowell engineered the move to Durham in 1892.

“There were some hurt feelings,” Gillispie said of the lingering sentiment in Trinity. “It was a big economic driver of the town, so it was not great news that they moved to Durham and took their faculty and students with them.”

Aside from a roadside historic marker, Craven’s grave and a gazebo housing a bell from the Trinity campus, there are few reminders left in the town of Trinity of the town’s role at the birthplace of what became Duke University.

Kittrell College

When Trinity College became Duke University in 1924, it began a process of sweeping change on campus. But before the Georgian style buildings of what’s now East Campus could rise, the domed library and most of the squat brick buildings that made up the old Trinity College campus needed to be removed.

Instead of being torn down, the structures found a second life on the campus of Kittrell College, around 40 miles northeast of Durham.

Instead of being torn down, the structures found a second life on the campus of Kittrell College, around 40 miles northeast of Durham.

Founded in 1886 in the small Vance County town of Kittrell, Kittrell College taught African-American men and women. Often facing financial hardship, the school benefitted from donations from the Duke family and guidance from administrators from Trinity College, some of whom served on Kittrell College’s board.

The most notable connection between the two schools came in the mid-1920s, when Trinity’s library – likely the most recognizable structure on campus at the time – and two other buildings were dismantled, moved and rebuilt on Kittrell College’s campus.

“We are to be congratulated on having fallen heirs to such splendid and valuable assets as are found in the material possessions already granted us,” John Russell Hawkins, Kittrell College’s business manager wrote in a 1925 letter to Duke officials. “But more than this do we value the friendship and cooperation found in the very fine spirit which has prompted you in your unselfish and broadminded service.”

After serving Kittrell College’s needs for nearly 50 years, the three buildings from Trinity College’s campus were destroyed by fire in 1972. Three years later, Kittrell College, which continued to face financial hurdles, closed.

The site is currently home to a vocational education center operated by Job Corps, part of the U.S. Department of Labor, and Duke’s connection to the site is largely forgotten.

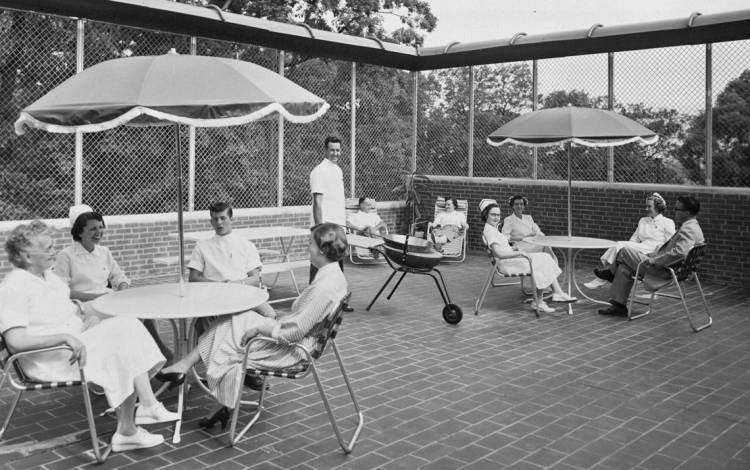

Highland Hospital

Tucked away in the Duke Medical Center Archives are papers, photos and blueprints related to Highland Hospital.

Through annual reports, budgets, meeting minutes, expansion plans, contracts and correspondence, it’s possible to get a good picture of the challenges that come with running a small mental health institution.

Through annual reports, budgets, meeting minutes, expansion plans, contracts and correspondence, it’s possible to get a good picture of the challenges that come with running a small mental health institution.

Cars broke down, kitchen equipment needed to be replaced and the distance between Durham and Asheville made communication and transportation difficult.

“It was really hard to run this institution, but they seemed to do it as a labor of love,” said DuRocher, the volunteer archivist with the Duke Medical Center Archives who worked closely with the material. “I really got a sense for how difficult it is to be an administrator and make a small hospital run. But they did it, and that was an amazing thing.”

Have a story idea or news to share? Share it with Working@Duke.